9/12/98

I cannot get over how kind the Turkish people are. At first, when they encounter an American in their presence, they’re surprised I’m not Christian, Aryan-looking, cold and condescending; when I try and talk in Turkish, no matter how badly it comes out, they’re thrilled I’m making the effort. Actually, sometimes it’s the surprising fidelity of my accent, along with the extreme kindness of Turks, which gets me into the most trouble. People think my Turkish is far better than it actually is, and they often happily launch into a rapid-fire conversation with me about anything and everything. Yesterday I asked one loquacious shopkeeper why the Ezan had sung six times instead of five; usually it only happens six times on a Friday – did someone on the island die? But I had committed an error: the ?mam is the singer, and the Ezan the song. So the shopkeeper thought I said Eczane, which means pharma

cy, and he also thought that because I talked about someone dying that there was something terribly urgent, and he frantically began to draw me a map to the pharmacy.

Having to constantly parse the arabesque for parts of grammar, as well as deriving context from hordes of Arabic and Farsi-derived words, is a tiring day’s work. And translation is always a challenge, as its suffix-additive grammar and arabesque sentence-structure are quite different that English. When Elif and I talk in English, I often hear people around us saying to each other in Turkish, “You talk to them in English.” “No, I’m too shy.” “No, come on, you talk to them.” “Some student you are!” And then I put them out of their misery with a “Merhaba,” and we talk a little in both languages. Last week I talked with a man on a boat who was pining about the glory days of the Ottoman empire. Here was a Turkish Minniver Cheevy, a history buff craving national glory of a misty poetic nature, rather than of a contemporary fascist state. As I got off the boat, he gave us the address of his workplace and told us if we ever wanted anything, anything at all, to stop by.

When we went East last month, I was again impressed by how Turks all over had no problem of my blatant American-ness (even finding a Korean War vet in Erzurum) – but also with how occupied the east seemed – such as Igdir, a town of Kurds patrolled by Turkish soldiers. What I didn’t realize is just how much Turkish ports are occupied by my own country. After we came back, we went to visit Elif’s dad in Antalya. We took a small boat (about 12 people) out on a cruise on the Mediterranean to some waterfalls and swimming holes. On the way, we passed by the American battleship Dwight D. Eisenhower. They’ve got 90 planes on it – it’s huge! It was the one where two weeks before, right there in Antalya, two of the American planes flying off it for practice collided mid-air, killing both pilots. Our captain, seeing that we were American, asked us if we wanted him to steer nearby, and we said yes. We didn’t know how nearby he’d go – we went right up to it and got to look inside – it was amazing – and we completed a half-circle around the thing, until a loudspeaker boomed, in English: “All non-authorized personnel please clear the vicinity.” That meant us, though our captain didn’t understand it. The loudspeaker boomed the same message, again, the voice sounding more urgent, and I was positive that we were going to be fired upon. We explained the message to our captain, and our boat sped off in haste.

******

1/29/2002

Yesterday we went to the Military Museum for a Janissary music concert. (The Janissaries were the Ottoman’s most elite troops, until they got so powerful they were violently abolished in the 1800’s). They entered the stage, in full colorful costume, and kept on coming, banging the heck out of their drums and wailing away on their Zurnas – such a deafening noise (and the stench of their bodies!) – you could see why a host country’s army would want to surrender right then and there. The handlebar-moustached man pounding on the lowest bass drum had a droopy-dog expression, like he was sorry that he was going to have to decapitate you, but it was only his job.

I don’t know how authentic the music was, but it sure was convincing – unlike the cheesy “Sultans of the Dance,” the Turkish take on the abominable “Lord of the Dance” which Cos took us all to see last month for Elif’s birthday. It was a real extravaganza, with about 140 dancers, with lots of lights and blaring music, authentic Turkish dances mixed in with modern bastardizations of the same. The production even provided buses to pick us up from the Asian side (where Dilek lives) to take us the 3 hours (10 kilometers) to the European side where the show was. We waited for the bus in a car-impoundment lot, and the traffic cops were very nice to us, smiling and offering us tea. What was nice is that they had some ringers mixed in there – real folkloric dancers as soloists, members of the ballet, etc. The star of the show, who plays the “Spirit of Turkey,” is the lead dancer of the Istanbul Government Opera and Ballet. He’s about 40.

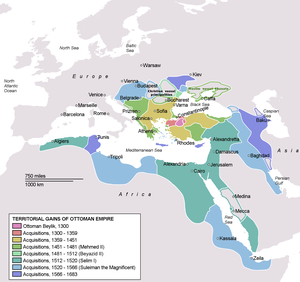

From these two shows, it seems like Turkey hasn’t really digested the implications of their Ottoman heritage. In fact, I’ve heard “Ottomanism” used here in so many different ways that I guess it just means something different to different people. For the more cosmopolitan Istanbullians, Ottoman times were a halcyon era where the art was more elaborate, the manner of speech and behavior more kind and gentle, and the cuisine more rich and not just influenced by the southeast. For religious people, Ottoman times are the high-water days of power, with a big Moslem empire spreading religion, where they captured Istanbul and were fair to foreigners under their own rule. For secular Turks, it’s a symbol of how many different races can be integrated under the protection of a powerful state. For fascists, “Ottomanism” is a clarion call to the return to the “glory days” of strong gonvernment. For people who have to navigate a bureaucratic structure (or ship their belongings!), it’s a symbol of a culture of bribery and corruption.

All of which cheerfully accepts or ignores the extreme violence of the Ottoman empire. Taking the view of Ottomanism as a beautiful melting pot ignores the extreme brutality of the forced assimilation. This happened throughout Turkish history, from when they took Rumeli and occupied the Balkans (which is why there are so many Muslims in Balkanian lands); to when 500 families were forced to move to Romania, and 500 Romanian families were sent to Edirne. The Ottomans found that moving around people controls them – and “Turkishizes” them. Elif’s father’s mother’s family were moved to Bulgaria when the Ottomans took over Bulgaria, and came back during the war when they lost Bulgaria. Elif’s mother’s father’s people were Turks who were forcibly moved to Crete, and they moved back when the Ottomans lost Greece. In recent years, Istanbul is becoming somehow less cosmopolitan, as Jews have left for Israel, and Greeks have left for Greece. Even today, this ideal of the benefits of forced assimilation is reflected in the national psyche. When we were filming “Coup,” one of our speakers told us that guards used to torture extreme leftists and rightists and then make them cellmates to break them down and get them to see that they all, in their twisted way, want what they think is best for the country – the policy was called “Mix it, fix it.” When you travel to the east, you’ll be in an entirely Kurdish area occupied by Turkish soldiers, and the mountains will have painted on them in huge letters, “Ne mutlu Turkum diyene.” (“How happy it is to say I’m a Turk.”)

In addition, the assimilation is hardly complete. While Turkey claims kinship with the Selcuks and with the other Turkic people of the eastern Asian plateau, there are Armenian and Kurdish minorities in the country who have to be explained for. Heavy-handed politicians have, in the past, put forth the claim that those minorities are actually Turkic peoples denying their heritage, a claim to which Elif’s dullard uncle Erturul subscribes. However, one glance into the eastern half of the country will reveal people and monuments unlike anything from the Greeks, Selcuks, Byzantiums, or Ottomans, and Turkey chooses to benignly ignore some, destroy others in the name of modernism, forbid naming children with ethnic names, etc. There are of course reasons for this repression – ignorance being one (many Istanbullians will have traveled all over the world but not to the eastern part of their own country), and the genuine threat of secession (such as Armenian land claims) or terrorism (the PKK) being another.

Turks are proud of being tolerant of ethnic differences (to the extent that they admit that they exist), even while beset by terrorism or threats of separatism. When the governments of Greece and Turkey get into a snit with each other, or when expatriate Armenians say they hate Turks, Greeks and Turkish families in Istanbul seem to get along just fine. This is probably because many citizens know that today’s fascist hawkish ultra-right-wing administration may be replaced by a neo-socialist one tomorrow.

In any event, the real differences that you find among Turks are not necessarily of ethnicity, but of class, and that’s a much more subtle thing to spot. Istanbullians pride themselves as not being Anatolians (from central Turkey), and among themselves, they discriminate between how long their families have been there, and in which “simt” (district) they reside. The classes serve each other and are together walking the same streets, but they don’t really intermingle as friends. Our landlord refused to rent another apartment to a woman wearing a headscarf because she was too “villager.” And when we were at a Turkish whorehouse in Savsat, Elif’s family called the whores “poor ‘yabancis’” – foreigners – even though they were plainly, indisputably Turkish.

Related articles

- Why did the Ottoman Empire attempt to reform itself (wiki.answers.com)

- Ottoman High-tide – The Balkans (broeder10.wordpress.com)

- 500 events celebrate Istanbul as Europe’s culture capital | British Airways – Travel Industry News (travelnews.britishairways.com)