Four hours later, at 5AM (on Monday the 24th), Dilek is so hot, sleepless, and livid that Co? would treat us this way that she wakes us up. We enter the stinky bathroom and use their shower, which has no showerhead, so we hose ourselves off like mental institution inmates. Co? arrives at 7, telling us how palatial and comfortable Hasan Bey’s accommodations were for him, and Dilek starts really letting him have it by some fairly timid whining. And just like after he abandoned us in Samsun when he told Dilek that she wasn’t from a village and knew what petrol smelled like, Co? claimed that his drive last night was heroic and that the Teacher’s house wasn’t really so bad.

Now pride may cometh before a fall, but if it doesn’t, you can always count on my wife to help push. Whereas before Elif had been nice-but-cold to Co?, as she always is when she doesn’t care for someone, I now find her screaming at him in the middle of the street that there was no earthly reason for us to be in this town, and that we could have stayed in a hotel in Artvin. I hang back and watch the delightful fireworks display, and, like a roulette ball finally coming to rest on its number, Elif settles on the theme that we’ve come over 200km out of our way for nothing and finally yells,“I’m not going to waste another day of my vacation for you to jerk off on having your ass kissed by a NOBODY.” Co? turned beet red and said Elif was embarrassing him in front of the people in the street, and Elif yelled, “The only people here are rednecks who want to FUCK us.”

This made Co? suddenly stop suggesting that we wait the three hours for Hasan Bey’s man to arrive so he could show us around, and instead he finds a random policeman and tells the cop that he’s a guest of the great Hasan Bey, and that could the cop please tell us where Hell’s River Gorge is? The cop, upon hearing the magic words “Hasan Bey,” insisted on showing us around personally on the city’s dime, and he hopped in the car. He stank so badly that when he started smoking I was actually thankful that there was another smell to distract me from his body odor. We got out at a gorge, less nice than the one at Sakklikent, and he helped us (literally held our hands as we climbed – his hands were huge) up the gorge, where we got to see the naturally-growing Fanta cans and Dorito bags. Co? kept up his pacifying avuncular routine and offered up the scop of taking us to see a church 40 km away on a road covered in boulders. Elif said in no uncertain terms that we had no interest in it, and that we wanted to leave.

Elif demanded that we head straight for Kars, and upon arrival, Co? bought a decade’s worth of honey, which of course took a while. The first shop we went to didn’t have Kars honey but another kind, and the fat boy behind the counter eating ice cream refused to bargain with Co?, saying that only his father had authority to do so. The boy then stepped right outside the door and dropped his ice cream wrapper on the street. He then went back into his store. Elif picked it up and followed him inside, smiled at him, and said softly, “Don’t you know what to do with the wrapper? This is what you’re supposed to do with a wrapper!” and threw it on the floor inside his store.

We went to the Kars tourist office to get the necessary permits for seeing Ani, which is 40 km southeast of Kars and literally on the Armenian border. It’s inside a restricted military zone, so there’s a bit of bureaucracy to go see it. First, we had to stop at the tourist information office to get the forms. The workers, upon seeing my passport of origin, flashed coprophagic smiles – they were giggling like children, literally reading “California” and “Marvin” out loud to each other.

I now realized that a window had just opened for me, a sudden opportunity for me to actually get to see Do?ubeyazit on the Iranian border, which Dilek and Co? had been too scared to go to. I knew from Co?’s behavior at Ardanuç that he was impressed by authority, and also that it was the job of these tourist officials to convince us that everything was quite safe and wonderful in Turkey, one great, happy Turkey uber alles. So I asked them if Do?ubeyazit was safe to go to, and they said, “Safe? No problem! It’s so beautiful – you’ve got to go! You can’t miss it!” And just like they were reciting lines in a play, our two travel companions were impressed, and the thing was settled: of course we were going. I left there floating on air, like I had achieved a major victory in being able to influence others, lead people, and shape my environment. And thus we were off, to the police station to get our forms endorsed, then to the museum to buy tickets, and, finally, to Ani.

When we entered the restricted zone, we had our passports and permits examined, and the sergeant at the entrance to Ani read us the riot act: stay by the monuments where we can see you, don’t go too far off the path, and if you even so much as point your camera in the direction of Armenia we’ll have to shoot you (and, after that, we may even confiscate your camera). None of this impressed me as much as his incredible blue eyes, unlike any I had ever seen before, especially on a dark-complexioned man, and I said to Elif in English, “What amazing eyes! He’s so beautiful!” He then went on, something about how you can’t go to the Covenant of the Virgins, and you can’t take pictures of the river, and blah blah blah, and I ask Elif, “I wonder why we can’t go there! Is it because of the archeological preservation, or is it for military purposes?” and finally the guy straightened up, stared directly at me, and said, in slow and perfect English, “Because we’re using it.” That shut me up. So off we went, and except for our friendly armed escort and two other tourists, we had the place completely to ourselves.

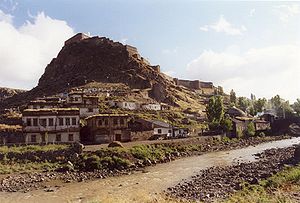

Ani became the capital of Armenia in the late 10th century, and for about five minutes, it was one of the world’s major cities. Byzantium annexed it 80 years later, and then the Selçuks took it, and then the Georgians, and then the Mongols, and finally the earthquakes came and roll the credits. But what a site! It was like seeing Efes without the tourists. Churches with wild frescos, crosses with snakes in them that looked like images from civilizations predates it by three millennium, cathedrals, a citadel – a real ghost town. We were there for hours. After the first five or so sites, the guards pretty much left us alone, except at the Menüçehir Camii, which was right on the river itself that was the border. We asked if we could climb up the minaret, and they said yes, which surprised me, but they made me leave their cameras with them. The climb up was, in large part, on broken stairs in pitch-dark, and in the parts where there was light, we saw some rats that made us wish for the dark again. On top, the view was phenomenal. The Rough Guide says that the minaret was closed because some tourist committed suicide by jumping off the top a few years ago, but once you’re up there, you realize that it’s more likely he just plain fell. While we were up there, Dilek, who stayed at the bottom, asked the guards what the huge military presence at Ani was for, because relations with Armenians are much improved since they got their own country from the former Soviet Union rather than from Turkish soil. The guards told her that a week and a half ago, they caught a few PKK members a little south of there, and after a brief friendly interview with them over some tea, the guerrillas had volunteered the information that they entered the country through the Armenian border.

Nearby the mosque, we saw some scorpions, and two archaeologists were working to uncover a graveyard. And there they were, sweeping dirt off bones, when suddenly, a baby’s skull popped out right in front of me, with its jaw hanging happily in the sun! What surprised me is how white the bones were after all these years, compared to the brownish mummies you see in museums. We asked them if we could take a picture of the graveyard. They said no and gave us a look that they wished we were some of the bones they were uncovering.

Back at Kars, we went again to buy even more honey from a bakkal. This took an hour not so much because of Co? but because the guy insisted on giving us all free juice and sugars and telling us his story. It turns out that he went to three (!) of the same schools as Elif in Istanbul, and this was his uncle’s store in which he helps out for the summer – for the rest of the year, he’s a ballet in the government folkloric dance troupe. How wonderful! He gets to jump around to cool steps, perhaps, I imagine, even juggling knives, and traveling all over the world to countries I will likely never go to – Azerbaijan, Iran, Romania. But who knows. He was complaining that he never gets to go to the exciting places like the U.S. or Japan, because Turkey’s President only wants to improve cultural relations with local countries.

That night, we met an Israeli couple and two Slovenian women tourists on the street, and we went to dinner with them. It turns out that the Israeli guy (Amir) had served and then worked in the army there for eight years, but he was more anti-Jewish-race-based state than I, and he was cocky about Israel’s permanent military superiority in the region. I found him to be a hoot – a big cuddly bear of a 30-year-old who fell madly in love with a different tourist every week. He liked to travel the world just to meet people (he would never go to Venezuela, Alaska, or New Zealand, because he’d rather go somewhere where there’s more people, less nature.) He went to Turkey by himself and met the Israeli woman he was with, in Cappadoccia! He just goes up to anyone who looks like a tourist, or who looks nice, and starts talking, male or female. He told me he thinks that people are inherently nice, and there’s a few bad people – which is just about the opposite of what Elif and I find to be true (that people are instinctual and that if they don’t eat you alive, it’s a testament to how successful they were socialized). And Amir holds this belief even after what happened to him on his second day in Turkey: he was standing on the Galata bridge in Istanbul, and two Egyptians walked up and started talking to him. They hung out together for three hours, talked to each other in English and Arabic, and entertained him with hilarious stories about their world travels. Then, the Egyptians suggested that they go out to dinner together at 9:30, so he went back to his hotel, shaved and showered, and met them for dinner. On the way, they went to a park and told him that it was an Egyptian custom for them to play the hosts and to offer yogurt-water and figs, but since there were no figs around, they knew of an Ayran-seller nearby. So one of them went to buy him Ayran and came back with the yogurt-drink, and they all drank, and the next thing he knew, it was a day later and he was waking up in his hotel bed from the best sleep he’d ever had in his life. Turns out they drugged his drink and stole his $600 Nikon camera and put him in a taxi, telling the driver to take him to his hotel because he was drunk, and the hotel paid the cab fare and carried him up the stairs, during which time the two Egyptians racked up $4000 on his Visa buying electronics. Amir’s card was insured, but his Israeli parents were freaked out, demanding he come home immediately. He says that the trip after that was the best he’d ever had, and the Turks were the nicest people he’d ever seen, and he didn’t mind the experience at all. All I could think of is how polite the Egyptians were – they didn’t take his passport, and they put him in a taxi and sent him back to his hotel – in America it wouldn’t quite turn out that way.

We all went out for tea later that evening and we couldn’t get a table outside in Kars – they were all full – and when one opened up, Elif and I ran to grab the seats, which made the Slovenians and Israelis laugh very much: “You really wear your country’s flag,” they said. The Israeli guy said he left the army after eight years because they would have promoted him from field work to administrative work, which he hated. I asked him what was field work, work in the field with maps, or what, and he answered “Intelligence.” It turns out that – and this is all he would tell me – his fluency in Arabic is due to his tenure in the Israeli army, and he is not allowed to travel to any of Israel’s Arabic neighbors until he is 55 as a security measure. Which is a real drag, because we really like him, and we’ll definitely visit him in Tel Aviv (perhaps soon, because Elif doesn’t need a visa to go there) – but since I’ve been to Israel twice, I was far more interested in schlepping him to Egypt with us, because he’s a lot of fun and fluent in Arabic. But he can’t go there anymore. Elif jokes that due to his naïveté and his experience with the two Egyptians in Istanbul, we may be even safer in Egypt if we go without him.