Elif and I went to visit her father Kadri, her stepmother Isik (who is twenty years younger than Kadri and looks startlingly like Elif), and her 6-year-old half-sister Eylul. They’re in the last few weeks of staying at their summer house in Tuzla. It’s one of a few small houses congregated around a common pool, neither well-made nor particularly luxurious, and they go to escape the heat and to gather with their summer friends. They rely on well-water, and Tuzla seems more hard-hit than any other area in Istanbul with water shortages. It seems silly that you’d spend a good part of your summer swimming at a second home when you often can’t use the toilet there.

We arrived in the late afternoon and were immediately greeted with a power outage. While Turkey’s infrastructure is faulty and aging, I’ve never been able to figure out what triggers outages in Istanbul at any given time; they happen on mild days as often as they do on days with extreme temperatures. You’ll be downloading a video email attachment of a guy hitting another guy over the head with a computer keyboard, or clearing pornography files off your father-in-law’s computer, and click! – the power’s out. Most Turkish homes are equipped with fluorescent lamps with rechargeable batteries that plug into the wall and automatically turn on when the power goes out (a couple of times a week).

We went swimming, towelled off, and began our dinner. Kadri loves to grill fish whenever we come, delighting in “forgetting” that we’re vegetarians. Elif’s stepmother Isik cuts the onions, which are served on the side and are crucial to the meal, so much so that once Isik walked out on a restaurant with us because they didn’t serve lemon and onion on the side of her grilled fish. We had arugula salad, and raki of course, and night rolled in. I was getting worried that we might be staying too late there, as Elif’s mother, who’s been divorced from him for a decade, still becomes quite jealous when we do.

The power still hadn’t resumed, so we lit candles and talked and drank. And the evening’s libations came to engender a certain sharpness in Kadri’s tongue, which proved an ill combination with Isik’s sensitivity to perceived slights. While her faculties and demeanor generally make Isik, to Kadri, a welcome relief from the whip-like firestorm of will that is Elif’s mother, tonight he was mocking Isik while looking at Elif and I in a conspiratorial way, which led to Isik crying and exiting the room. Kadri’s response: “Women, they come, they go; I’ve had two wives and I’ll have a third if necessary.”

When Isik returned, there was still no electricity, but hurt feelings were in abundance, so Kadri’s sister Nebahat decided to call the ghosts. Nebahat had polio as a youth, so one of her legs is shorter than the other, and she serves as the family’s conduit to the spirit world. She communicates with the beyond and will tell you all about death, ghosts, reincarnation, and telepathy if given the slightest provocation. (She levitates, too.)

Ghost-calling is the perfect activity for an evening with a Turkish family without electricity. Creating the Ouija board is a low-tech endeavor – tearing pieces of paper – but a very serious one. Isik is most serious of all. She believes, as do all except Elif, Kadri, and I. Nebahat will actually push the cup, Elif explains; although everyone present including Nebahat knows that she will actually push the cup, they remain firmly convinced not that she’s a prophet, but that the ghost indeed is guiding her hand. While I may be a poor medium, I’m a game audience, and I can take minutes. I find the idea of meaning appearing letter by letter and changing midstream lovely. And I love to watch the women’s efforts at solidifying the family bond while the men couldn’t care less. Kadri is “rahat” (comfortable) but useless in this interaction, as no money is involved.

The ghost is giving information about Isik’s mother’s husband, who just separated from her. Nebahat takes dictation from the ghost; Isik’s mother mother weeps at the information. The ghost addresses others and can slap and then forgive and be forgiven.

THE GHOST (to Isik): “You are meaning well, but it’s not showing…”

At this point, it’s hard to tell the believers from the nonbelievers; simple people are receiving koans and hard truths alike. Isik is angry at the ghost, who has now likened her to a machine. Nebahat, the medium, is untouchable. They’re casual but not skeptical, easily slipping into the beneficent fiction. Elif’s half-sister Eylul, who’s 7 years old, is bored; the ghost had better say something to her quick – but placation is not the ghost’s purpose; maybe the girl is better off asleep, and Nebahat and Eylul don’t seem to like each other much.

THE GHOST: “…But don’t worry about that, because your future is completely clean.”

THE GHOST then addresses me. He does not know me but says I am happy. I am grateful that he will speak to us at all, however briefly, many years from now, one thousand and ten years ago. The ghost now spells I-B-S-E-N. He spells it repeatedly, and then says, “Don’t start your job without reading Ibsen.” And then: “Have hope.” And then: “You have to check [not read] the newspapers with a big hope. CHECK the newspapers all the time, without sleep, without getting tired. You’re very smart; the job will find you.” (Oh shit, is this a money thing again?) And finally: “But run after it so much and take it seriously.”

THE GHOST, to Elif: “If you know the technique, you will be successful. Your spirit is clean, but you can’t forget the technique.”

Nebahat: “I want a 5-minute break for a cigarette.”

Ertugrul, Nebahat’s asinine brother-in-law: “How can you take a break without consulting the ghost? You’re not taking it seriously.”

Nebahat then consults with THE GHOST, who then proceeds to spell out: “Don’t listen to your brother-in-law who doesn’t take it seriously himself.”

THE GHOST was right: I am happy.

The power comes on.

Isik says, maybe the ghost is tired. Kadri laughs at her that the ghost doesn’t have a body and can never be tired. This makes Isik nervous, and she tells him to be serious. Ertugrul The Redneck sits on the couch away from us and says ssh. Kadri now makes fun of him, saying he’s the ghost’s lawyer. Elif translates this for me, and I laugh with Elif and try to share the laugh with Kadri, but the way knowledge traded is crucial: Kadri looks at me with a half-smile and quickly glances away, not knowing if I know the story of how Ertugrul had screwed him really maliciously in a business deal fifteen years ago.

Nebahat said to THE GHOST, “We will pray for your soul. We are going to sleep. Please go,” and she turned the cup over.

***

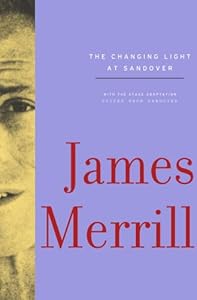

I woke up the next morning at Elif’s mother’s house, brushed my teeth, and had a vague feeling that the voice of Nebahat was inside my toothbrush, talking to me. I thought I had gone crazy from last night’s proceedings, as well as from reading James Merrill’s The Changing Light at Sandover, a 500-page Ouija poem. She asked me through my toothbrush, “Can I talk to you?” I said, “Well, what’s up?” And she answered: “Can you understand my Turkish? Elif doesn’t believe in this stuff, she’s very strong, she doesn’t believe in anything.” I told her spirit that I wasn’t sure that her atheism in and of itself meant strength, but that in any case, I was due back on planet Earth, and that the next time we’d talk to each other would be in person. She thanked me and I rinsed out my mouth.

An hour later, Elif’s mother’s sisters came over for breakfast, and I made the mistake of casually mentioning in conversation that Nebahat had just that morning spoken to me telepathically as I brushed my teeth. Boy, were they pissed!

“Of course she spoke to you – it’s just like her to do a thing like that,” said one aunt. Her husband: “Psychic powers exist, and if she has them, which I’m not sure she does, she should use them properly.” The aunt: “She hypnotizes you, puts you in a trance with her slow, steady, sweet voice, and sucks you into the whole thing, whether you like it or not.” Another aunt: “She only uses these powers to feel special.”